For almost the past month, key computer systems serving the government of Baltimore, Md. have been held hostage by a ransomware strain known as “Robbinhood.” Media publications have cited sources saying the Robbinhood version that hit Baltimore city computers was powered by “Eternal Blue,” a hacking tool developed by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and leaked online in 2017. But new analysis suggests that while Eternal Blue could have been used to spread the infection, the Robbinhood malware itself contains no traces of it.

On May 25, The New York Times cited unnamed security experts briefed on the attack who blamed the ransomware’s spread on the Eternal Blue exploit, which was linked to the global WannaCry ransomware outbreak in May 2017.

That story prompted a denial from the NSA that Eternal Blue was somehow used in the Baltimore attack. It also moved Baltimore City Council President Brandon Scott to write the Maryland governor asking for federal disaster assistance and reimbursement as a result.

But according to Joe Stewart, a seasoned malware analyst now consulting with security firm Armor, the malicious software used in the Baltimore attack does not contain any Eternal Blue exploit code. Stewart said he obtained a sample of the malware that he was able to confirm was connected to the Baltimore incident.

“We took a look at it and found a pretty vanilla ransomware binary,” Stewart said. “It doesn’t even have any means of spreading across networks on its own.”

“We took a look at it and found a pretty vanilla ransomware binary,” Stewart said. “It doesn’t even have any means of spreading across networks on its own.”

Stewart said while it’s still possible that the Eternal Blue exploit was somehow used to propagate the Robbinhood ransomware, it’s not terribly likely. Stewart said in a typical breach that leads to a ransomware outbreak, the intruders will attempt to leverage a single infection and use it as a jumping-off point to compromise critical systems on the breached network that would allow the malware to be installed on a large number of systems simultaneously.

“It certainly wouldn’t be the go-to exploit if your objective was to identify critical systems and then only when you’re ready launch the attack so you can do it all at once,” Stewart said. “At this point, Eternal Blue is probably going to be detected by internal [security] systems, or the target might already be patched for it.”

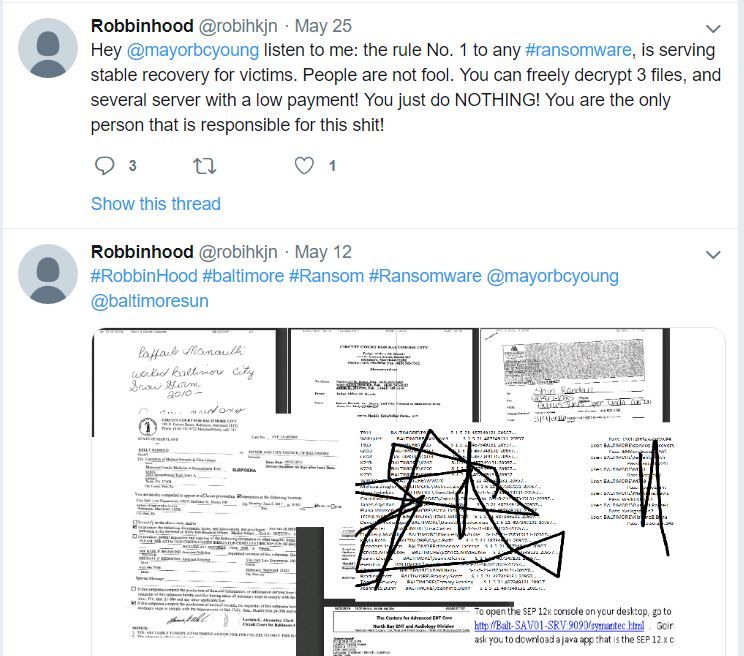

It is not known who is behind the Baltimore ransomware attack, but Armor said it was confident that the bad actor(s) in this case were the same individual(s) using the now-suspended twitter account @Robihkjn (Robbinhood). Until it was suspended at around 3:00 p.m. ET today (June 3), the @Robihkjn account had been taunting the mayor of Baltimore and city council members, who have refused to pay the ransom demand of 13 bitcoin — approximately $100,000.

In several of those tweets, the Twitter account could be seen posting links to documents allegedly stolen from Baltimore city government systems, ostensibly to both prove that those behind the Twitter account were responsible for the attack, and possibly to suggest what may happen to more of those documents if the city refuses to pay up by the payment deadline set by the extortionists — currently June 7, 2019 (the attackers postponed that deadline once already).

Some of @robihkjn’s tweets taunting Baltimore city leaders over non-payment of the $100,000 ransomware demand. The tweets included links to images of documents allegedly stolen by the intruders.

Over the past few days, however, the tweets from @Robinhkjn have grown more frequent and profanity-laced, directed at Baltimore’s leaders. The account also began tagging dozens of reporters and news organizations on Twitter.

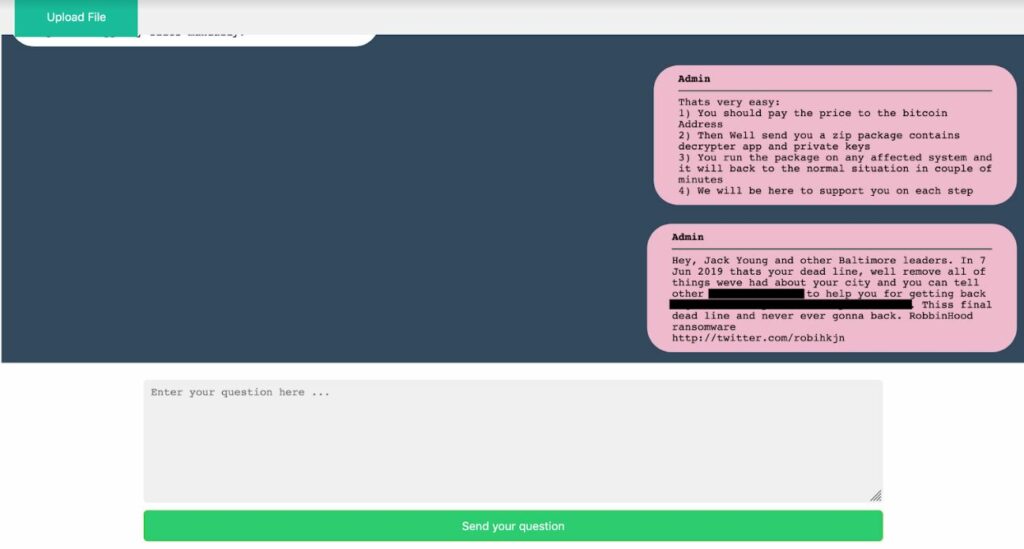

Stewart said the @Robinhkjn Twitter account may be part of an ongoing campaign by the attackers to promote their own Robbinhood ransomware-as-a-service offering. According to Armor’s analysis, Robbinhood comes with multiple HTML templates that can be used to substitute different variables of the ransom demand, such as the ransom amount and the .onion address that victims can use to negotiate with the extortionists or pay a ransom demand.

“We’ve come to the conclusion Robbinhood was set up to be a multi-tenant ransomware-as-a-service offering,” Stewart said. “And we’re wondering if maybe this is all an effort to raise the name recognition of the malware so the authors can then go on the Dark Web and advertise it.”

This redacted message is present on the Dark Web panel set up by the extortionists to accept payment for the Baltimore ransomware incident and to field inquiries or pleas from them. The message repeats the last tweet from the @robihkjn Twitter account and conclusively ties that account to the attackers. Image: Armor.

There was one other potential — albeit likely intentional — clue that Stewart said he found in his analysis of the malware: Its code included the text string “Valery.” While this detail by itself is not particularly interesting, Stewart said an earlier version of the GandCrab ransomware strain would place a photo of a Russian man named Valery Sinyaev in every existing folder where it would encrypt files. PCRisk.com, the company that blogged about this connection to the GandCrab variant, asserts Mr. Sinyaev is a respectable finance professional who has nothing to do with GandCrab.

The timing of the GandCrab connection is notable because just last week, the creators of GandCrab announced they were shutting down their ransomware-as-a-service product, allegedly after earning more than $2 billion in ransom payments.

Finally, since we’re on the subject of major ransomware attacks and scary exploits, it’s a good time to remind readers about the importance of applying the latest security updates from Microsoft, which last month took the unusual step of releasing security updates for unsupported but still widely-used Windows operating systems like XP and Windows 2003. Microsoft did this to head off another WannaCry-like outbreak from mass-exploitation of a newly discovered flaw that Redmond called imminently “wormable.”

That vulnerability exists in Windows XP, Windows 2003, Windows 7, Windows Server 2008 R2, and Windows Server 2008. In a reminder about the urgency of patching this bug, Microsoft on May 30 published a post saying while it hasn’t seen any widespread exploitation of the flaw yet, it took about two months after Microsoft released a fix for the Eternal Blue exploit in March 2017 for WannaCry to surface.

“Almost two months passed between the release of fixes for the EternalBlue vulnerability and when ransomware attacks began,” Microsoft warned. “Despite having nearly 60 days to patch their systems, many customers had not. A significant number of these customers were infected by the ransomware.”